The main goal is to make it easier to build end-to-endstreaming applications, which integrate with storage, serving systems, and batch jobs in a consistent and fault-tolerant way

SELECT action, WINDOW(time, “1 hour”), COUNT(*)

FROM events

GROUP BY action, WINDOW(time, “1 hour”)

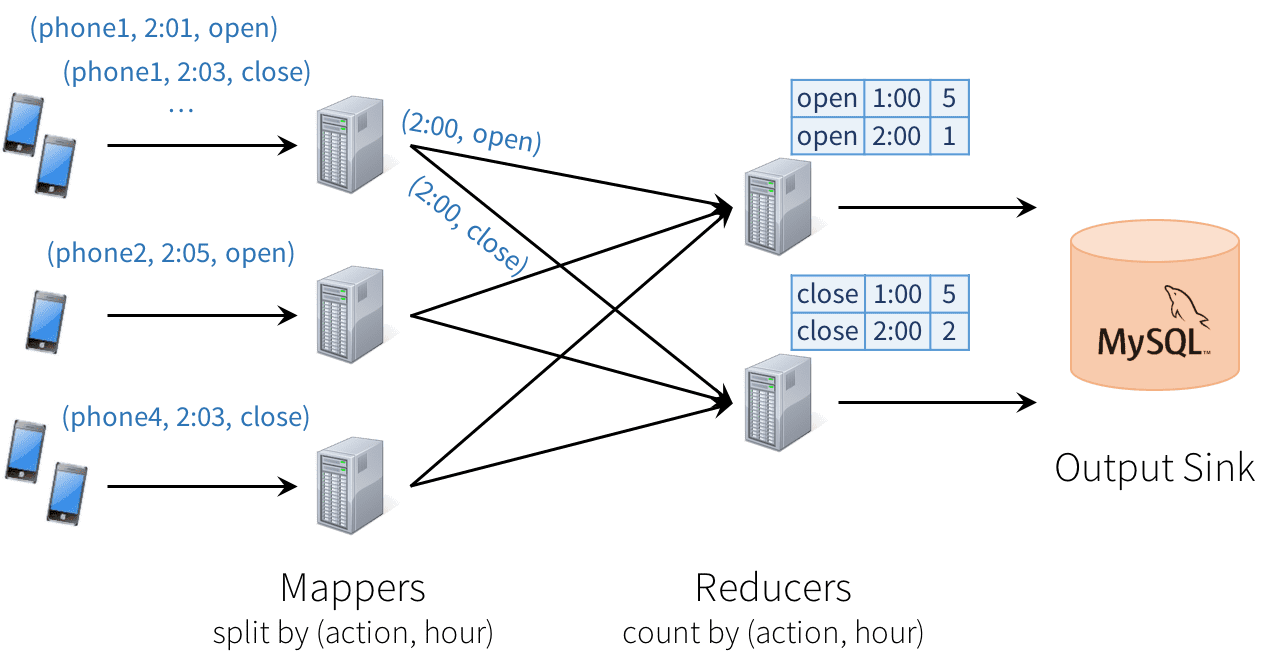

Unfortunately, this type of design can introduce quite a few challenges:

- Consistency: This distributed design can cause records to be processed in one part of the system before they’re processed in another, leading to nonsensical results. For example, suppose our app sends an “open” event when users open it, and a “close” event when closed. If the reducer node responsible for “open” is slower than the one for “close”, we might see a higher total count of “closes” than “opens” in MySQL, which would not make sense. The image above actually shows one such example.

- Fault tolerance: What happens if one of the mappers or reducers fails? A reducer should not count an action in MySQL twice, but should somehow know how to request old data from the mappers when it comes up. Streaming engines go through a great deal of trouble to provide strong semantics here, at least within the engine. In many engines, however, keeping the result consistent in external storage is left to the user.

- Out-of-order data: In the real world, data from different sources can come out of order: for example, a phone might upload its data hours late if it’s out of coverage. Just writing the reducer operators to assume data arrives in order of time fields will not work—they need to be prepared to receive out-of-order data, and to update the results in MySQL accordingly.

Structured Streaming Model

In Structured Streaming, we tackle the issue of semantics head-on by making a strong guarantee about the system: at any time, the output of the application is equivalent to executing a batch job on a prefix of the data. For example, in our monitoring application, the result table in MySQL will always be equivalent to taking a prefix of each phone’s update stream (whatever data made it to the system so far) and running the SQL query we showed above. There will never be “open” events counted faster than “close” events, duplicate updates on failure, etc. Structured Streaming automatically handles consistency and reliability both within the engine and in interactions with external systems (e.g. updating MySQL transactionally).

This prefix integrity guarantee makes it easy to reason about the three challenges we identified. In particular:

- Output tables are always consistent with all the records in a prefix of the data. For example, as long as each phone uploads its data as a sequential stream (e.g., to the same partition in Apache Kafka), we will always process and count its events in order.

- Fault tolerance is handled holistically by Structured Streaming, including in interactions with output sinks. This was a major goal in supporting continuous applications.

- The effect of out-of-order data is clear. We know that the job outputs counts grouped by action and time for a prefix of the stream. If we later receive more data, we might see a time field for an hour in the past, and we will simply update its respective row in MySQL.

Users just describe the query they want to run, the input and output locations, and optionally a few more details. The system then runs their query incrementally, maintaining enough state to recover from failure, keep the results consistent in external storage, etc. For example, here is how to write our streaming monitoring application:

- // Read data continuously from an S3 location

- val inputDF = spark.readStream.json(“s3://logs”)

- // Do operations using the standard DataFrame API and write to MySQL

- inputDF.groupBy($“action”, window($“time”, “1 hour”)).count()

- .writeStream.format(“jdbc”)

- .start(“jdbc:mysql//…”)

Model Details

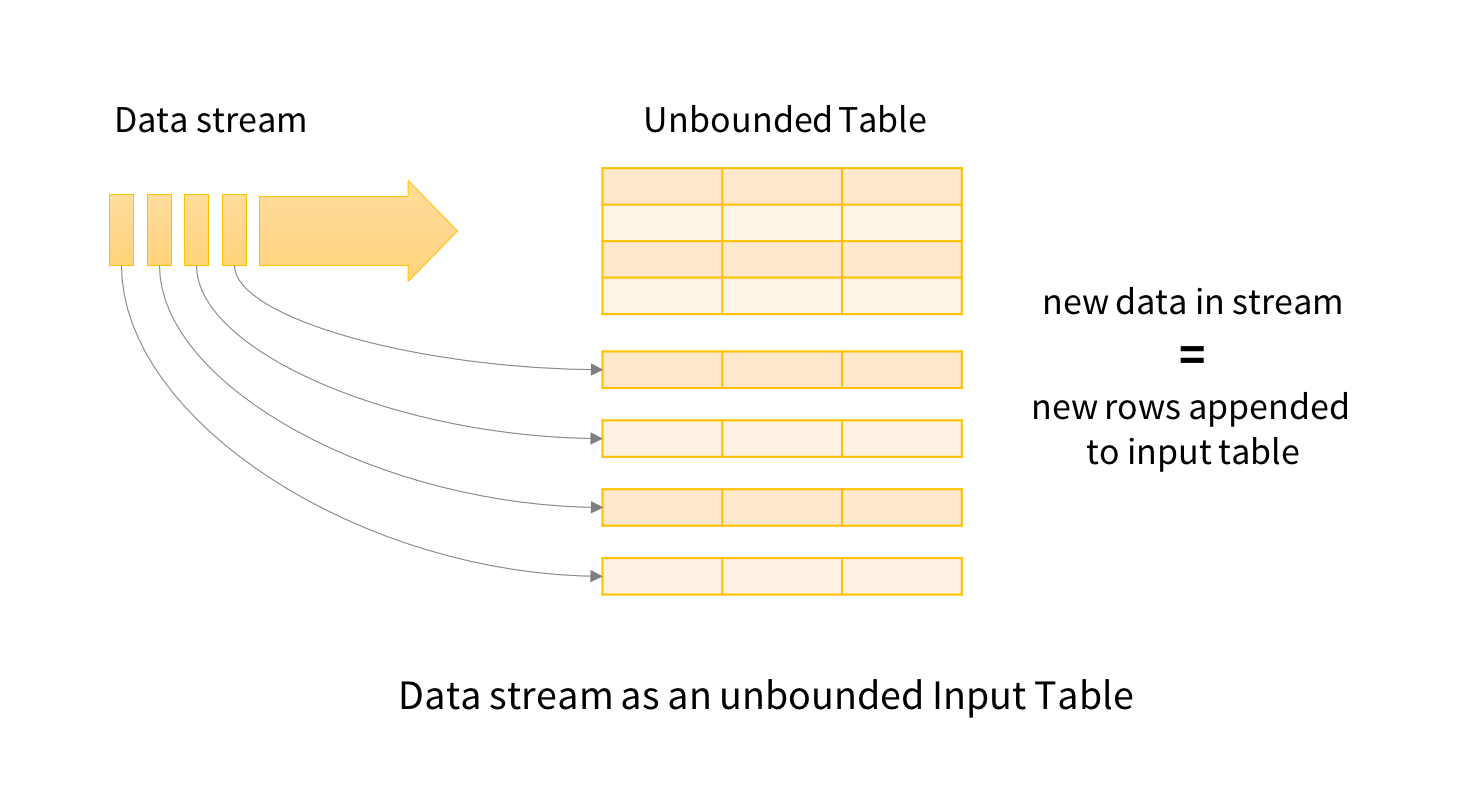

Conceptually, Structured Streaming treats all the data arriving as an unbounded input table. Each new item in the stream is like a row appended to the input table. We won’t actually retain all the input, but our results will be equivalent to having all of it and running a batch job.

The developer then defines a query on this input table, as if it were a static table, to compute a final result table that will be written to an output sink. Spark automatically converts this batch-like query to a streaming execution plan. This is called incrementalization: Spark figures out what state needs to be maintained to update the result each time a record arrives. Finally, developers specify triggers to control when to update the results. Each time a trigger fires, Spark checks for new data (new row in the input table), and incrementally updates the result.

The last part of the model is output modes. Each time the result table is updated, the developer wants to write the changes to an external system, such as S3, HDFS, or a database. We usually want to write output incrementally. For this purpose, Structured Streaming provides three output modes:

- Append: Only the new rows appended to the result table since the last trigger will be written to the external storage. This is applicable only on queries where existing rows in the result table cannot change (e.g. a map on an input stream).

- Complete: The entire updated result table will be written to external storage.

- Update: Only the rows that were updated in the result table since the last trigger will be changed in the external storage. This mode works for output sinks that can be updated in place, such as a MySQL table.

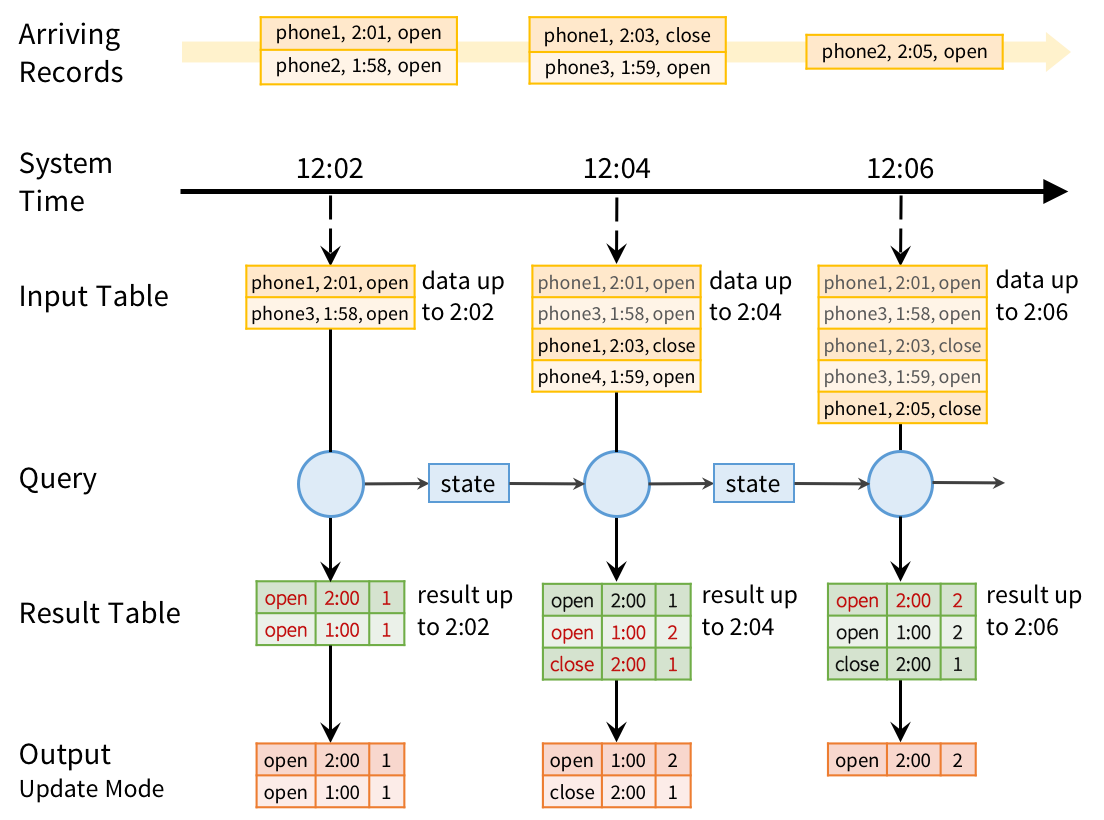

To run this query incrementally, Spark will maintain some state with the counts for each pair so far, and update when new records arrive. For each record changed, it will then output data according to its output mode. The figure below shows this execution using the Update output mode:

However, the prefix integrity guarantee in Structured Streaming ensures that we process the records from each source in the order they arrive. For example, because phone1’s “close” event arrives after its “open” event, we will always update the “open” count before we update the “close” count.

Fault Recovery and Storage System Requirements

Structured Streaming keeps its results valid even if machines fail. To do this, it places two requirements on the input sources and output sinks:

- Input sources must be replayable, so that recent data can be re-read if the job crashes. For example, message buses like Amazon Kinesis and Apache Kafka are replayable, as is the file system input source. Only a few minutes’ worth of data needs to be retained; Structured Streaming will maintain its own internal state after that.

- Output sinks must support transactional updates, so that the system can make a set of records appear atomically. The current version of Structured Streaming implements this for file sinks, and we also plan to add it for common databases and key-value stores.

We found that most Spark applications already use sinks and sources with these properties, because users want their jobs to be reliable.

Apart from these requirements, Structured Streaming will manage its internal state in a reliable storage system, such as S3 or HDFS, to store data such as the running counts in our example. Given these properties, Structured Streaming will enforce prefix integrity end-to-end.

It also adds new operators for windowed aggregation and for setting parameters of the execution model (e.g. output modes). In Apache Spark 2.0, we’ve built an alpha version of the system with the core APIs. More operators, such as sessionization, will come in future releases.

Streams in Structured Streaming are represented as DataFrames or Datasets with the isStreaming property set to true

- val inputDF = spark.readStream.json(“s3://logs”)

- val countsDF = inputDF.groupBy($“action”, window($“time”, “1 hour”))

- .count()

The new DataFrame countsDF is our result table, which has the columns action, window, and count, and will be continuously updated when the query is started. Note that this transformation would give hourly counts even if inputDF was a static table. This allows developers to test their business logic on static datasets and seamless apply them on streaming data without changing the logic.

Finally, we tell the engine to write this table to a sink and start the streaming computation.

- val query = countsDF.writeStream.format(“jdbc”).start(“jdbc://…”)

The returned query is a StreamingQuery, a handle to the active streaming execution and can be used to manage and monitor the execution.

Windowed Aggregations on Event Time

Streaming applications often need to compute data on various types of windows, including sliding windows, which overlap with each other (e.g. a 1-hour window that advances every 5 minutes), and tumbling windows, which do not (e.g. just every hour). In Structured Streaming, windowing is simply represented as a group-by. Each input event can be mapped to one or more windows, and simply results in updating one or more result table rows.

Windows can be specified using the window function in DataFrames. For example, we could change our monitoring job to count actions by sliding windows as follows:

- inputDF.groupBy($“action”, window($“time”, “1 hour”, “5 minutes”))

- .count()

Whereas our previous application outputted results of the form (hour, action, count), this new one will output results of the form (window, action, count), such as (“1:10-2:10”, “open”, 17). If a late record arrives, we will update all the corresponding windows in MySQL. And unlike in many other systems, windowing is not just a special operator for streaming computations; we can run the same code in a batch job to group data in the same way.

Windowed aggregation is one area where we will continue to expand Structured Streaming. In particular, in Spark 2.1, we plan to add watermarks, a feature for dropping overly old data when sufficient time has passed. Without this type of feature, the system might have to track state for all old windows, which would not scale as the application runs. In addition, we plan to add support for session-based windows, i.e. grouping the events from one source into variable-length sessions according to business logic.

Joining Streams with Static Data

Because Structured Streaming simply uses the DataFrame API, it is straightforward to join a stream against a static DataFrame, such as an Apache Hive table:

- // Bring in data about each customer from a static “customers” table,

- // then join it with a streaming DataFrame

- val customersDF = spark.table(“customers”)

- inputDF.join(customersDF, “customer_id”)

- .groupBy($“customer_name”, hour($“time”))

- .count()

Interactive Queries

Structured Streaming can expose results directly to interactive queries through Spark’s JDBC server. In Spark 2.0, there is a rudimentary “memory” output sink for this purpose that is not designed for large data volumes. However, in future releases, this will let you write query results to an in-memory Spark SQL table, and run queries directly against it.

- // Save our previous counts query to an in-memory table

- countsDF.writeStream.format(“memory”)

- .queryName(“counts”)

- .outputMode(“complete”)

- .start()

- // Then any thread can query the table using SQL

- sql(“select sum(count) from counts where action=’login'”)